OBJECTIVE

The Jackson Area Transit Authority (JATA) provides bus service on nine routes throughout the city. Routes and schedules are printed and distributed on the buses, but there has been little effort to share this information through newer media channels. As a result, people don't have the basic information they need to ride the bus. This is an obvious first step towards JATAs goal of engaging riders and potential riders.

JATA needs to identify more ways for potential and current riders of the bus to answer the simple question, "when will the bus come and where will it take me?"

This project was undertaken as a part of Citizen Interaction Design, a collaboration between the University of Michigan School of Information and the City of Jackson.

SO TO BEGIN...

OUT IN THE FIELD...

So we decided to spend an afternoon riding the busses, talking to passengers, and contextual-inquiry-ing transit employees.

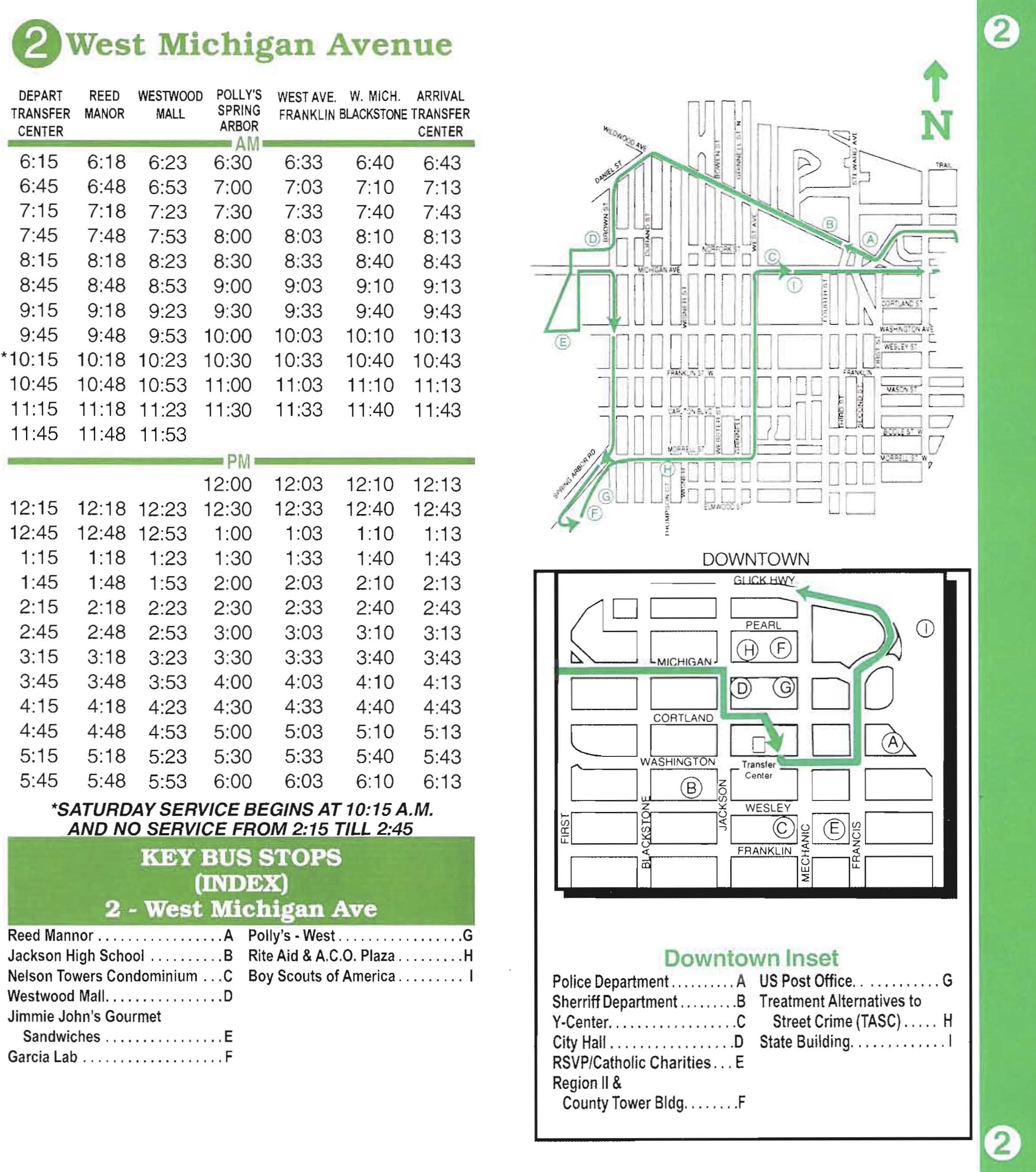

We sat around in the JATA's Transfer Station for a while, observing the flow of people in and out of the station; copies of their pamphlet were placed behind display cases in the sitting area, and an information desk was situated in the northwest corner of the I-shaped room. In talking to the employee behind the window, who was responsible for fielding questions not only in person but also over the phone, we learned that people seldom request pamphlets (which they began charging for to cover the cost of printing), that the busses are generally on-time and reliable (which is great because of the whole 30-minute-loop thing they have going on), and that calls regarding bus performance usually came in only during times of inclement weather (like the Polar Vortex).

Then we hopped on a bus, where we noticed that there were very few bus shelters and that many of the bus stops were just a JATA placard bolted to a tree; we also noticed that inside the bus shelter was the transit information pamphlet, opened to that route's page and sandwiched inside the display panel. Passengers had a sense of how to navigate the system, but the people we observed and spoke to were also frequent riders. The bus we were on happened to be running behind schedule, and the bus driver radioed to the Transfer Center that we would be a minute or two late; a major factor of communications since the system's hub-and-spoke model contributed to a high volume of passengers changing busses.

TO THE DRAWING TABLE

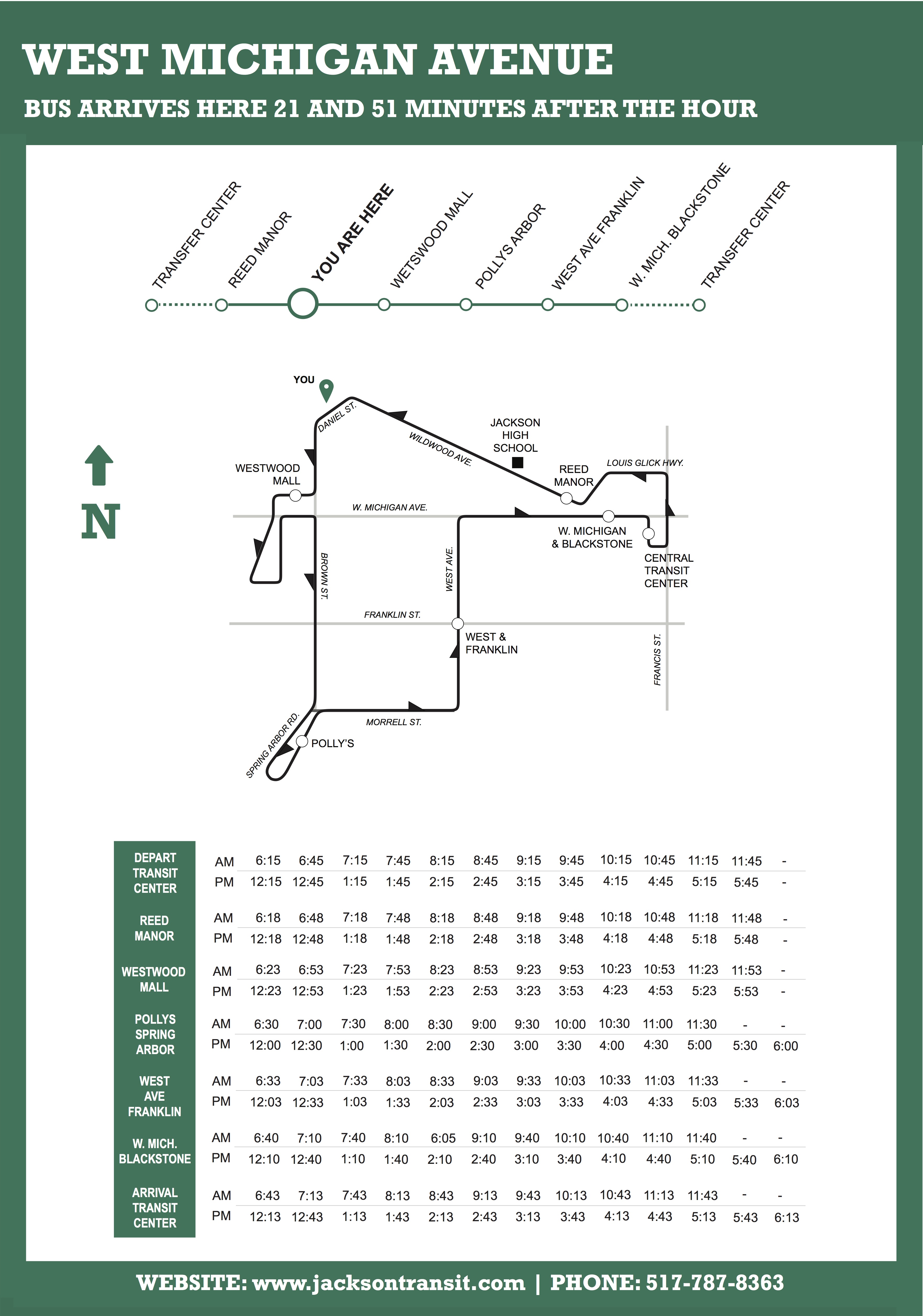

As far as communicating route information to riders, the most obvious gap was a lack of information at bus stops and shelters. Because the busses have a fairly solid on-time performance and, in the case of seven of the routes, go to each bus stop twice an hour half an hour apart, there was little need to investigate live tracking of the busses; we designed signage to be used as placards at bus stops and posters in bus shelters. The signs' main call-to-action is when on the hour the bus arrives at that particular stop, and the rest of the route's information is then presented as reference.

We also built a prototype for a responsive website that could accomodate an alert system that could, in turn, also send those alerts via text message and social media. The agency's relative lack of resources and the general demographics of the City of Jackson made this the most pragmatic and effective solution: users can still get information via their smartphones without needing to install additional applications, and the agency only has one code base to maintain.